Big Story

‘Man power,’ ‘man hours’ and other phrases to ix-nay from your iased-bay vocabulary

Seemingly innocuous gendered language in the workplace is actually super toxic

Billionaire Ken Fisher uttered some pretty despicable comments at a financial conference last week, likening building trust with a client to the process of “trying to get into a girl’s pants,” among other sexist remarks. The money manager is now facing major business repercussions, with clients pulling hundreds of millions of dollars from Fisher Investments.

Given the urgency of the other issues women face in the workplace, complaining about gendered language may seem like misspent energy, particularly when it doesn’t go as far as Fisher did and is of the more commonplace variety, e.g. “How many man hours will that project take?” But that is far from the case, and a dangerous misconception, experts agree.

“Humans use language as a social tool just as we use it to communicate,” said Jessica Nicholas, a sociolinguist based out of Illinois. “Although it can sometimes be subtle, many forms of societal discrimination and prejudice are reflected in language.”

While there are many languages that give gender to nouns (Spanish, Portuguese, French and so on), gendered language is, in fact, more insidious in languages like English where technically everything is gender neutral, linguistic researchers say.

Consider everyday words and phrases such as “man power,” “mankind,” “spokesman,” “chairman” and “man hours” — using the male modifier to represent all of humankind in its respective roles actually has the effect of “making women disappear in mental representations,” according to research from social psychology experts Michela Menegatti and Monica Rubini.

Industry insiders say that in the tech sphere, which is growing by leaps and bounds, the way this sort of language is bandied about is particularly egregious.

Therese Littleton, who recently finished a consulting gig at EQUALS, a nonprofit working to bridge the gender divide in tech, said phrases like “grow a pair” and “ballsy” are still ubiquitous in the workplace and alienate women.

Littleton worked for Amazon when it was just starting out in the late ‘90s and said that, while “dude,” for instance, doesn’t even trigger a blip on the radar, she still found it damaging in the early stages of her career. “Being called ‘dude’ for the first time in my life and having it be unironically the way you speak to anyone in the tech industry really stuck out,” Littleton said. “[B]eing a woman automatically puts you in the not cool pile, until you act like a bro.”

Littleton noted that she heard a lot of lewd so-called “locker-room talk” at the tech behemoth during that period. “It was a prevalent notion that if you were a woman, and you didn’t want to be offended, you didn’t go to the area where the coders had their cubicles,” she said. “It was assumed that they were crass and crude. It was a ‘boys-will-be-boys’ sort of thing. If you wanted to get in, you had to participate at the toxic masculinity level.”

And despite the rise of the #MeToo movement, that toxic masculinity in language is very clearly still alive and doing very well across industries today. To wit, Fisher’s comment last week that anyone not comfortable discussing genitalia should not be in the finance industry. How many women — or men, for that matter — actually want to be discussing genitalia at work?

Hep Svajda, a product manager for a prominent software provider in Silicon Valley (she chose not to publicly disclose which company), said language consistently affects work life. “There is plenty of problematic language in tech terminology: male and female ports, and so-called ‘femtech.’ You have problematic language in regard to ‘master and slave,’ terms commonly used to refer to computer drive or partition relationships,” said Svajda, who left the tech industry for a period in the early 2000s because of sexism. “Like many engineering trades, there are all manners of innocuously named terms that end up being used in dirty jokes: finger, dongle, hot swap, penetration testing.”

Svajda added that while phrases like “two guys in a garage” and “IT guy” may have been apt originally, their continued usage contributes to the reasons the tech sphere struggles more than many other industries to overcome gender bias.

“Exclusionary language is one of the more overt ways people can set boundaries or barriers between the in-group and the out-group,” said sociolinguist Nicholas. “Especially when there is a gender-neutral alternative [like ‘IT person’], making the choice to use a gendered word or expression is not merely a matter of word choice; it clearly communicates that people outside the specified gender are not welcome in that position.”

April S., who declined to give her last name, works for an international nonprofit trying to increase Internet access globally. She said the characterization of what and who is “dumb” versus “genius” comes up a lot in discussions about technology in ways that are often disparaging towards women. One might not think much of saying, “explain this in a way my grandmother or mother would understand it,” she said, but the fact that the phrase is so common points to the deeper discrimination in the tech sphere.

“It’s never the proverbial grandfather or father, and it reinforces the idea that women are incapable of understanding tech, or even logical concepts,” she said, adding that she finds it especially depressing that this language often comes from young people, who presumably grew up with more enlightened ideas on genders.

Men, meanwhile, are often deemed “genius” for things for which women would get no accolades. “The genius label comes up a lot to describe men working in tech, from startup founders to programmers. I’ve never heard that label applied to a woman in tech, not once in my more than 20 years in this field,” she said. “The men I’ve seen described as geniuses are smart or have good ideas or are good at coding — all labels that apply to many women doing the same exact things.”

Svajda also noted how unfair it is that addressing language issues becomes yet an additional task for women, with the accompanying risk of getting fired or labeled as a troublemaker. “Often when people address workplace oppression, they are actually taking on a second unpaid job of advocate, and many times have to bear damage to their careers because of it,” Svajda said. “Whether it’s being known as a troublemaker, angry, touchy, looking for something to get mad about…Or the actual extra work of sitting in meetings, serving on panels, or participating in other ways to force change.”

So, what’s to be done? Making a conscious effort to strike the use of male terminology as the norm is a good start for companies, and Human Resources departments should be the first to adopt the change, according to a study by researchers at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada. The most harmful instances of gender inequalities are often enacted in HR practices because those policies affect everything from hiring, to pay and promotion.

To deconstruct this systemic discrimination, companies need to first look at the wording of employment advertisements, which, the study showed, are frequently drafted in language oriented toward men. Also, remove all gendered language from employee evaluations and make sure to explicitly lay out objective performance goals on all reviews in order to strip them of subjectivity.

On the individual level, VP of Marketplace at Facebook Deb Liu writes that committing to tracking usage of gendered phrases like, “right-hand man,” “man-made,” “two-man rule” and so on during the work week and then publicly correcting yourself is a good approach to correcting unconscious bias in language — and, it simultaneously alerts colleagues to the issue. Using replacement terms such as, respectively, “right-hand person,” “synthetic” or “machine-made” and “two-person rule” may sound awkward at first, but as more and more employees get on board with gender-neutral language, such terminology will become the norm. That’s how the evolution of language has always worked.

As is clear from the Fisher incident — and likely countless recent incidents of that sort that have gone unreported — there is much work left to be done in eliminating discriminatory language at work.

When Svajda returned to the tech world in the 2010s, she found that the struggle against workplace sexism in its many forms, including more insidious manifestations such as word choice, had not diminished. Now, she says, she’s always performing an “internal cost-analysis monologue,” analyzing the harm versus good of bringing attention to these constant microaggressions.

Two years into #MeToo and the attendant focus on gender equality in the workplace, Svajda —like many women in tech and other high-risk, high-reward industries — feels she’s facing an impossible choice: “The biggest issue is just the constant battle of whether to prioritize my career or fight against sexism.”

You may also like...

Editor’s Picks

And just like that…

It’s 2022. Happy New Year! Can we still say that? Maybe just for this one last day? We’re happy to...

Wow, that naughty list is looong🧑🎄

The naughty or nice list Can you IMAGINE how long this newsletter would be if we actually got into the...

Time’s up on Time’s Up? – Cuomo’s cringey bro code – Casual misogyny of ‘Succession’

Is Time’s Up just getting a glow-up, or a legit overhaul? The status of Time’s Up, the nonprofit dedicated to...

Trending

Boss Betty✊: Why board talk isn’t boring – Amazon sued (again) for gender bias – Pinterest aims to put a pin in bias

Why we never get bored with board talk Business has replaced government as the most trusted institution in the world,...

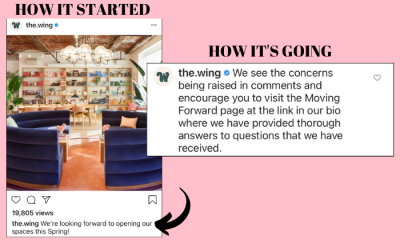

The Wing is reopening and some ex-employees — and former members — are not happy

The Wing posted on Instagram Wednesday that they would be reopening next week, starting with one of their Manhattan locations....

It’s Equal Pay Day, the ‘holiday’ we cannot wait to get rid of!

Hahaha, so cute that a year ago we asked, “What will post-pandemic, Equal Pay Day 2021 look like?” and here...