Finance

The Arjuna playbook, AKA, going next level in the fight for equal pay

When veteran investor Natasha Lamb stood up to present at Facebook’s annual shareholder meeting in 2017, she faced the backs of the four board members — yes, including Zuck and Sheryl, too — seated on the stage.

“Only 27 percent of our management team is female,” said Lamb, co-founder of the investment firm Arjuna Capital, adding that women made up just 33 percent of Facebook’s overall workforce. The numbers she cited were pulled from the social network’s 2016 diversity report, which covered demographics but did not include gender pay gap numbers, a major shortfall she was seeking to rectify.

As she talked, the company’s usually hoody-clad CEO — seated in the half-circle of chairs on stage facing the moderator’s podium — turned his head slightly to see the woman whose voice filled the hall over the loudspeakers. “Mark Zuckerberg must have been like, ‘Who is this woman?’” Lamb said, laughing at the memory.

By now, he knows the answer — as do many of the CEOs of the top tech, banking and retail firms in the country. Lamb’s team at Arjuna, which has $211 million in assets under management, has used its equity stakes to successfully compel companies including Apple, Google and Citigroup to be more transparent about their gender pay gap numbers and create a roadmap for closing them. As for Lamb’s proposal that year that Facebook disclose its pay gap numbers, it didn’t pass. Nor did it pass in 2018, nor at the most recent shareholder meeting in May.

But while Arjuna has made steady progress on the pay gap issue since its founding in 2013, by Lamb’s own admission many of the companies it’s involved with have only done the bare minimum or produced data that obfuscates the real story.

When Google did an analysis of its compensation data across gender and race in 2018, it concluded that there was no gap, posting a big fat zero for “the number of statistically significant pay differences between Googlers” on a corporate blog. The major problem? It failed to include the highest-paid 11 percent of employees in the analysis.

Cut to this year and Arjuna’s shareholder proposal that Google report on their global median gender pay gap — that is, the difference between the median earnings of all male employees versus female employees. The proposal included a breakdown by race as well. It was voted down by about 89 percent at Google’s annual meeting in June. This was the fourth time Arjuna had made a shareholder pay gap proposal that failed at Google.

But Arjuna’s far from done — they’re already putting together proposals for the 2020 proxy season, the period when most publicly traded companies hold their annual shareholders meetings.

The Arjuna playbook

Any shareholder that owns at least 1 percent of a company’s shares (or $2,000 worth — whichever is less), can submit proposals that are voted on at the firm’s annual shareholder meeting. Arjuna uses this tool liberally to influence companies to make decisions that are both socially and economically beneficial.

The sustainable investment firm has submitted shareholder proposals to 46 companies in the tech, finance and consumer goods industries since 2014, asking that they release a pay equity analysis across genders and minority groups. Often, the proposal process opens up a dialogue between the investors and the company’s board, which may lead to the desired outcome, and the proposal never goes to a vote.

Half of the companies Arjuna has approached have acquiesced to varying degrees, according to a scorecard released by the investment firm earlier this year. Out of the 12 tech companies in the mix, nine have released wage data and eight have committed to annual disclosures. Some companies release the data in a detailed report, or publish the results in a public statement or in their annual shareholder presentations.

Mind the gap — and bolster the bottom line

There’s growing evidence that transparency is effective at closing the wage gap. A study from the University of Copenhagen found that in Denmark, where companies have been required to disclose pay equity data since 2006, the disclosures reduced the wage gap by 7 percent.

Margret Bjarnadottir, a researcher at the University of Maryland, works with companies to help them analyze their compensation data and correct the wage gap. “You can’t fix what you don’t measure,” she said. “But it’s not enough to measure it, you have to take steps to correct it.”

Bjarnadottir said that when companies begin looking at discrepancies in pay, it forces them to review the more endemic issues at the root of the gap — like why some roles are valued more than others and general hiring practices — to figure out why one demographic group might be falling behind.

As an investor, Lamb makes the business case for equal pay, saying the research shows that more diverse teams lead to better outcomes. “If you have more women in leadership positions, and on teams, and more ethnic and racial diversity on teams, that leads to more innovation and better business decision making,” Lamb said. “It leads to better financial performance, better return on equity, better stock, price performance, and those, of course, are all things that investors care about.”

The evidence supports her assertions. Reports from firms including McKinsey and Morgan Stanley found that the companies that were the most diverse at the management level were more likely to have financial returns above the industry mean. The research shows that diverse teams are more innovative, and that diversity is to some degree self-propagating — diverse workplaces attract more non-male and non-white job candidates. A survey by PricewaterhouseCoopers showed that 61 percent of top female candidates consider workplace diversity when deciding where to work.

Winds of change

Lamb admitted it can be difficult to untangle the business case from the cultural winds. As the glare of the spotlight on corporate culture has grown increasingly brighter over the years, consumer expectations of the companies they engage with have evolved and affected purchasing decisions. When Uber gained a reputation for discrimination against its female employees, many consumers deleted the ride-sharing app and switched to competitors. And that, of course, has affected what shareholders prioritize.

Just five years ago, when Lamb filed her first pay equity transparency proposal with eBay, it received almost no notice. It got just 8 percent of the shareholder vote.

The next year, in preparation for the 2016 proxy season, Arjuna filed the same pay equity proposal with nine tech behemoths, including Amazon, Apple and Intel. All the proposals requested information on minority pay as well.

By then, the zeitgeist was moving ever so slowly towards Arjuna’s corner — by the time their proposals hit the media in early 2016, Oscar-winner Patricia Arquette had brought up equal pay at the Academy Awards; Salesforce, unprompted, had promised to release detailed compensation numbers; and a woman was the frontrunner for president.

With Lamb’s persistence and the cultural tailwinds, six of the nine companies released their numbers that year, and only three holdouts — Facebook, Google and eBay—went to a vote. “It was like a domino effect in the industry,” Lamb said. At the eBay shareholder meeting, the proposal passed with 51 percent of the vote, though shareholders and board members at both Facebook and Google voted no.

Moving on Wall Street

Arjuna went to Wall Street in 2017 and filed the same pay gap disclosure proposal with a number of banks and financial institutions, the industry with the highest wage discrepancy across gender. Women in finance made 70 cents on the dollar compared with men in 2018, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, while the median pay gap across industries was 81 cents.

They were met with resistance across the board until Citigroup bit the bullet and announced in January 2018 that it would release its numbers. Immediately, many of the other financial institutions began following suit.

It’s important to note that there are two ways to report the pay gap, both of which are equally significant, said Lamb. “One is how women are paid versus their direct peers for the work that they’re doing. And then the other way to look at it is what women on average are paid at a company versus men on average.”

The first is what’s known as the equal-pay-for-equal-work gap, or the difference in pay for the same job, and the second is the median pay gap, which is the median pay for all women compared to all men at the firm and lays bare how few women are in leadership positions.

While both are important, the latter number reveals more about the impact of the systemic issues that keep women crowded on the lower rungs of the ladder, ranging from cultural exclusion and necessary career disruptions (e.g., childbirth) to straight up discrimination. The Congressional Joint Economic Committee estimates that discrimination may account for 40 percent of the pay gap. “The median gap really shows the structural issue of who’s holding the high-paying jobs,” Lamb said. “It’s an unflattering metric.”

This year, Arjuna went back to 12 companies to request not only the equal-pay-for-equal-work numbers, but also the overall median. Unsurprisingly, this is not a data point companies want to share.

Once again, Citigroup was the first to reveal its median pay gap following Arjuna’s push. While the financial services firm reported just a 1 percent gap for equal work, it has a 29 percent gap overall; on average men at the company take home $1 for every $0.71 that a woman takes home. “It’s that kind of transparency and honest disclosure that actually needs to change,” Lamb said, lauding the bank’s forthcomingness while chastising those that did not follow suit. “Because when you put it out there, you’re like, ‘Yeah, that’s not right!’”

The remaining companies opposed Arjuna’s proposals, and they failed during this spring’s proxy season.

Legislating and litigating change

Arjuna’s efforts are one piece of a larger puzzle in closing the wage gap — the last several years have seen some progress in both the legislative and legal arenas.

Google has been sued by both former employees and the Department of Labor over its pay practices. “We found systemic compensation disparities against women pretty much across the entire workforce,” Janette Wipper, a Labor Department regional director, testified during the case in 2017.

In the U.K., new regulations imposed a couple of years ago forced Google to disclose details that clearly illustrated the pay disparities as workers climb the company’s corporate ladder. The results showed that female Googlers make up just one-fifth of the top 25 percent of earners at Google. In plain English, that means about 80 percent of Google employees bringing down the big bucks are men.

“Google believes that compensation should be based on what one does, and not who one is,” the company wrote in a proxy statement this year, explaining why its board of directors opposed Arjuna’s pay disclosure proposal.

In the U.S., the Obama administration instituted a regulation requiring companies of 100 employees or more to report their gender and minority compensation data to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The requirement was frozen under the Trump Administration in 2017, but this April a court order reinstated it and companies have until the end of September to report the numbers to the agency. Many companies say the reporting is unreasonably onerous, while advocates say the regulation needs more teeth.

Meanwhile, the Paycheck Fairness Act — which was reintroduced this year and passed the House in March, but is unlikely to make it past the Senate — puts forth additional measures to help reduce the pay gap. The provisions include prohibiting companies from asking prospective new employees about previous compensation, and making it harder for companies to prosecute employees who share information about their compensation.

A wolf in Lamb’s clothing

If the government won’t force pay transparency, Arjuna will, Lamb said. She’s been an ardent supporter of socially responsible investing for years — back before there was even a real term for it. In fact, Lamb got her MBA at one of the first schools in the country to give it one: Seattle’s Pinchot University (now Presidio Graduate School).

At Pinchot, she met and later worked for Joan Bavaria, the founder of Trillium Asset Management, reportedly the first socially responsible investment firm. As far back as the 1980s, Bavaria was making the unorthodox case that investment firms could wield their financial influence to advocate for corporate responsibility, and that such a strategy could be profitable.

“She was kind of like the grandmother, or the mother, of sustainable investing,” Lamb said. “And I met her and she really inspired me to go down this path.”

And she’s not veering from it. But these days, she’s much less alone.

Equal pay has become a global rallying cry, quite literally. After the U.S. women’s soccer team won its fourth World Cup in early July, the Paris stadium crowds broke out in a chant of “equal pay.” In response, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez jokingly tweeted that instead of asking for equal pay, “We should demand they be paid at least twice as much.” Pro player Megan Rapinoe has been a vocal advocate in the gender discrimination suit against the United States Soccer Federation. A handful of the 2020 candidates have floated ideas on how to approach the workplace gender inequity issue.

It helps to have that kind of star power on board, but to affect real change takes the knowledge and commitment of people like Lamb, who are willing to take the fight directly to corporate executives. Whether more of them will begin to listen remains to be seen.

Editor’s Picks

And just like that…

It’s 2022. Happy New Year! Can we still say that? Maybe just for this one last day? We’re happy to...

Wow, that naughty list is looong🧑🎄

The naughty or nice list Can you IMAGINE how long this newsletter would be if we actually got into the...

Time’s up on Time’s Up? – Cuomo’s cringey bro code – Casual misogyny of ‘Succession’

Is Time’s Up just getting a glow-up, or a legit overhaul? The status of Time’s Up, the nonprofit dedicated to...

Trending

Boss Betty✊: Why board talk isn’t boring – Amazon sued (again) for gender bias – Pinterest aims to put a pin in bias

Why we never get bored with board talk Business has replaced government as the most trusted institution in the world,...

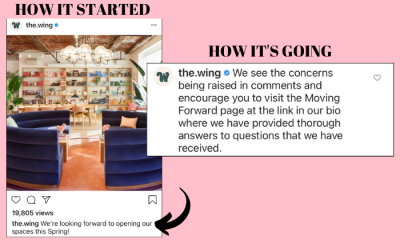

The Wing is reopening and some ex-employees — and former members — are not happy

The Wing posted on Instagram Wednesday that they would be reopening next week, starting with one of their Manhattan locations....

It’s Equal Pay Day, the ‘holiday’ we cannot wait to get rid of!

Hahaha, so cute that a year ago we asked, “What will post-pandemic, Equal Pay Day 2021 look like?” and here...